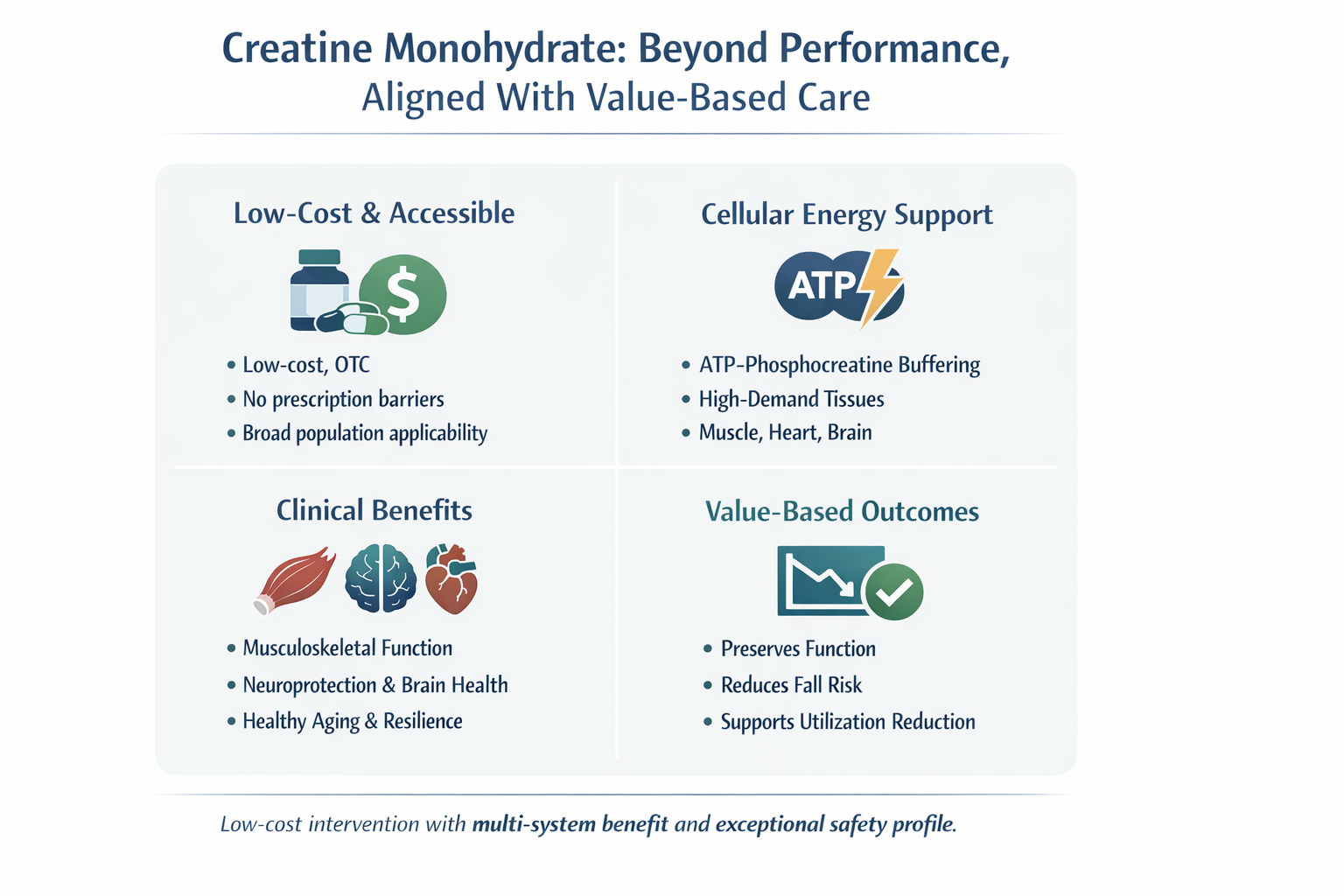

For decades, creatine monohydrate (CM) has been associated with bodybuilding and elite athletics – a limiting perspective increasingly incompatible with modern data. As healthcare systems transition toward value-based care, clinicians are being asked to prioritize interventions that are clinically effective, safe across populations, and economically efficient. Within this framework, the American Academy of Value-Based Care (AAVBC) spotlights therapies that improve longitudinal outcomes while reducing downstream utilization.1

A robust body of literature now identifies creatine as a fundamental metabolic regulator with multiple mechanisms which benefits cardiovascular health, neuroprotection, and the management of age-related physiological decline.2 Creatine (N-(aminoiminomethyl) -N-methyl glycine) is a naturally occurring nitrogenous compound essential to cellular energy homeostasis.2 More than 1,000 peer-reviewed publications support its safety and efficacy across athletic and non-athletic populations, including older adults and patients with chronic disease.2 This expanding evidence base demands us to reconsider creatine as a metabolic support therapy with clinically meaningful functional effects, not merely a performance supplement.

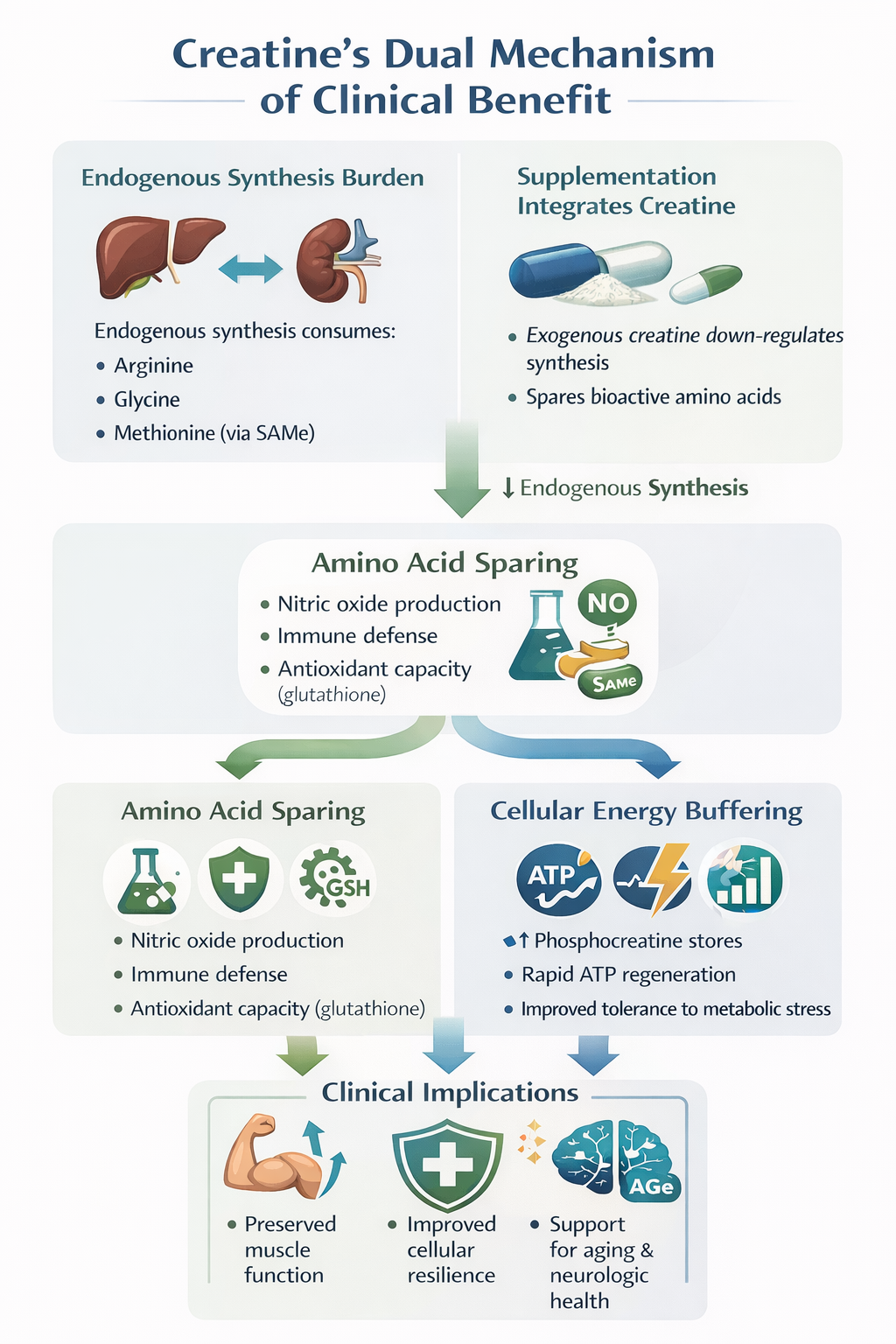

Endogenous creatine synthesis occurs via a two-step inter-organ pathway involving the kidneys and liver.3 The enzyme L-arginine: glycine amidinotransferase (AGAT) converts arginine and glycine to guanidinoacetate (GAA), which is subsequently methylated by guanidinoacetate N-methyltransferase (GAMT) using S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) as a methyl donor.3 This process imposes a significant metabolic burden.

In a typical 70-kg adult, endogenous creatine synthesis (~1.5–2 g/day) consumes approximately 46% of daily arginine intake, 36% of glycine, and up to 87% of methionine requirements.4 By providing exogenous creatine monohydrate through supplementation, the body can downregulate this production, effectively "sparing" these bioactive amino acids for other critical functions.3, 4

This sparing effect has meaningful clinical implications. Preserved arginine availability supports nitric oxide (NO) production and immune defense (NO is a killer of pathogenic bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses), while methionine conservation maintains SAMe pools required for DNA methylation and glutathione synthesis, the body’s principal antioxidant system.4,5 From a value-based care perspective, this represents a rare example of a single low-cost intervention improving multiple metabolic pathways simultaneously.

Creatine’s primary biological role is as a high-energy phosphate buffer in tissues with fluctuating energy demands, including skeletal muscle, myocardium, and the brain.6 After cellular uptake via the SLC6A8 creatine transporter, creatine is phosphorylated by creatine kinase to phosphocreatine (PCr).6

During periods of metabolic stress, PCr rapidly donates phosphate groups to regenerate adenosine triphosphate (ATP):

PCr + ADP (low energy) + H⁺ ⇌ ATP (high energy) + Cr

This system functions as both a temporal buffer, sustaining ATP during sudden energy demand, and a spatial buffer, shuttling high-energy phosphates from mitochondria to cytosolic sites of utilization.6 Supplementation increases intramuscular and cerebral PCr stores by approximately 10 - 40%, improving tolerance to metabolic stress without altering resting ATP levels.2

Aging is associated with a progressive decline in creatine and PCr availability, particularly in skeletal muscle.7 Research has shown that Phosphocreatine regeneration rates decrease by approximately 8% per decade after age 30. This reduction is closely associated with the atrophy of Type II (fast-twitch) muscle fibers, which are highly dependent on the phosphagen system for power.6, 7

Randomized trials demonstrate that creatine supplementation combined with resistance training produces significantly greater gains in lean mass, strength, and functional performance in older adults compared with resistance training alone.8 These improvements are clinically relevant: lower-body strength is a key determinant of fall risk, fracture incidence, and subsequent hospitalization in aging populations.7, 8 For value-based organizations accountable for total cost of care, preserving musculoskeletal function directly supports utilization reduction.

Concerns regarding kidney injury stem largely from misinterpretation of serum creatinine levels. Creatinine is a breakdown product of creatine; supplementation may raise serum creatinine without impairing glomerular filtration rate or causing renal pathology.2, 9 Long-term studies using doses up to 30 g/day for up to five years demonstrate that creatine is safe in individuals with normal renal function.2, 9

Creatine increases intracellular water content within muscle cells to maintain osmotic balance.2 This phenomenon reflects cellular hydration rather than pathologic fluid retention and may act as an anabolic signal promoting protein synthesis.7 Maintenance dosing (3–5 g/day) does not result in clinically meaningful long-term increases in total body water relative to lean mass.2, 10

Speculation regarding hair loss originates from a single small study reporting increased dihydrotestosterone (DHT) levels that remained within normal clinical ranges and did not measure alopecia.9 Subsequent studies have failed to replicate this finding.9

The brain accounts for roughly 20% of total energy consumption despite representing only ~2% of body weight.11 Creatine enhances cerebral energy buffering and reduces vulnerability to ischemia, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction.6, 11 Although brain uptake is slower than in skeletal muscle, higher or prolonged dosing (10–20 g/day) can meaningfully increase brain creatine stores.11

Emerging evidence supports creatine’s potential beneficial role in:

While not a disease-modifying therapy, creatine represents a biologically plausible neuroprotective adjunct.

Creatine’s medical legitimacy is most clearly demonstrated in gyrate atrophy, a rare inherited disorder (roughly 1 in 1,000,000 people globally) caused by ornithine aminotransferase deficiency.25 Excess ornithine inhibits AGAT, leading to systemic creatine deficiency and progressive muscle atrophy.25,26 In this context, creatine monohydrate functions as a necessary medical food, restoring muscle PCr levels and improving functional outcomes.26,27

Evidence-based protocols are straightforward:

Creatine monohydrate remains the gold standard; alternative formulations offer no consistent clinical advantage.2

Creatine monohydrate exemplifies the type of intervention value-based healthcare should prioritize: low cost, broad physiologic relevance, exceptional safety, and measurable functional benefit. Far from being limited to athletic performance, creatine supports musculoskeletal integrity, cerebral bioenergetics, immune metabolism, and healthy aging.2,6,7

The evidence no longer supports relegating creatine to the supplement aisle. In modern clinical practice, it represents a rational, evidence-aligned metabolic therapy that fits squarely within value-based care principles.

1. American Academy of Value-Based Care. Learning Hub and regulatory standards. Accessed January 20, 2026. https://aavbc.org

2. Kreider RB, Kalman DS, Antonio J, et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2017;14:18. Published June 13, 2017. doi:10.1186/s12970-017-0173-z 3. Brosnan ME, Brosnan JT. The role of dietary creatine. Amino Acids. 2016;48(8):1785-1791. doi:10.1007/s00726-016-2188-1

4. Nedeljkovic D, Ostojic SM. Dietary exposure to creatine-precursor amino acids in the general population. Amino Acids. 2025;57(1):29. Published May 24, 2025. doi:10.1007/s00726-025-03460-7

5. Ren W, Rajendran R, Zhao Y, et al. Amino acids as mediators of metabolic cross talk between host and pathogen. Front Immunol. 2018;9:319. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00319 6. Wallimann T, Tokarska-Schlattner M, Schlattner U. The creatine kinase system and pleiotropic effects of creatine. Amino Acids. 2011;40(5):1271-1296. doi:10.1007/s00726-011-0877-3

7. Candow DG, Forbes SC, Chilibeck PD, Cornish SM, Antonio J, Kreider RB. Effectiveness of creatine supplementation on aging muscle and bone: focus on falls prevention and inflammation. J Clin Med. 2019;8(4):488. Published April 11, 2019. doi:10.3390/jcm8040488 8. Chilibeck PD, Kaviani M, Candow DG, Zello GA. Effect of creatine supplementation during resistance training on lean tissue mass and muscular strength in older adults: a meta-analysis. Open Access J Sports Med. 2017;8:213-226. Published November 2, 2017. doi:10.2147/OAJSM.S123529

9. Antonio J, Candow DG, Forbes SC, et al. Common questions and misconceptions about creatine supplementation: what does the scientific evidence really show? J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2021;18(1):13. Published February 8, 2021. doi:10.1186/s12970-021-00412-w

10. Ribeiro AS, Aoki MS, Schoenfeld BJ, et al. Effects of creatine supplementation on total body water in resistance-trained men. Int J Sports Med. 2017;38(6):425-432. doi:10.1055/s-0042-122117

11. Dolan E, Gualano B, Rawson ES. Beyond muscle: creatine supplementation and brain function. Eur J Sport Sci. 2019;19(8):1023-1033. doi:10.1080/17461391.2019.1595631

12. Avgerinos KI, Spyrou N, Mantzoros CS, et al. Eight weeks of creatine monohydrate supplementation in Alzheimer disease: a pilot study. Front Nutr. 2025;12:1298473. doi:10.3389/fnut.2025.1298473

13. Balfoort BM, et al. Molecular mechanisms underlying gyrate atrophy. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2021;44(5):1234-1246. doi:10.1002/jimd.12345

14. Heinänen K, et al. Creatine corrects muscle 31P spectrum in gyrate atrophy. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22(9):1223-1230.

15. Hultman E, Söderlund K, Timmons JA, et al. Muscle creatine loading in men. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81(1):232-237. doi:10.1152/jappl.1996.81.1.232